Deconstructivism is a linguistic movements of the middle to late twentieth century that focused on the primacy of language. Essentially, the deconstructivist believed that an individual’s perception was predetermined by their thoughts, knowledge, and cultural background. Classifications became the defining factor of perception, with some even denying the possibility of visual imagination altogether. This linguistic movement became the basis for Postmodern architecture, as it also adopted the viewpoint that language and therefore symbolism were essential building blocks of architecture.

The contemporary or orthodox view, taken by philosophers and psychologists in the past two decades, is that perception and language are not the same thing, and perception or conceptualization does not occur instantaneously. Rather, people first perceive, then we think, and thirdly we conceptualize or express thoughts. The distinction between these two methods of perceiving space is important. The architectural postmodernists used symbolism to give meaning to their architectural concepts. If one accepts the contemporary view, one can deduce that language-based architecture was an intellectual exercise in building a series of symbolic objects. The problem is that this symbolism could not be universally read, and the architecture offered little in terms of objective spatial qualities. The contemporary view allows for the design and experience of space without needing stories and symbolism. Without needing an allegory, the power and primacy of space becomes much more important. This creates the scenario where architects do not need to reference something outside of architecture. Architecture can then be made up of simple, proto architectural elements.

Importance of Scale

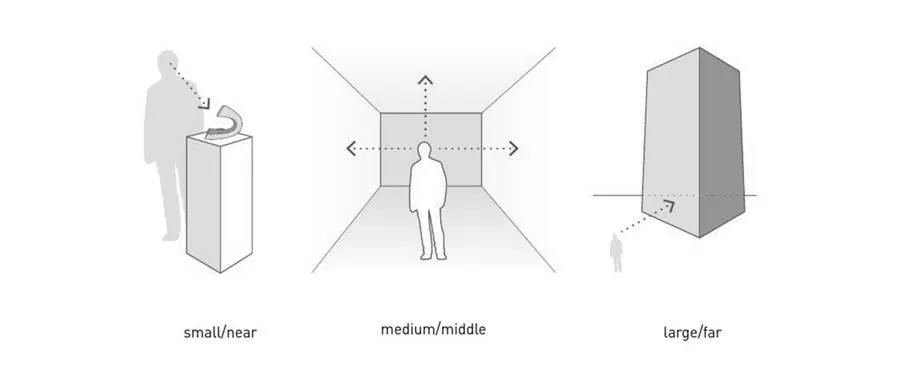

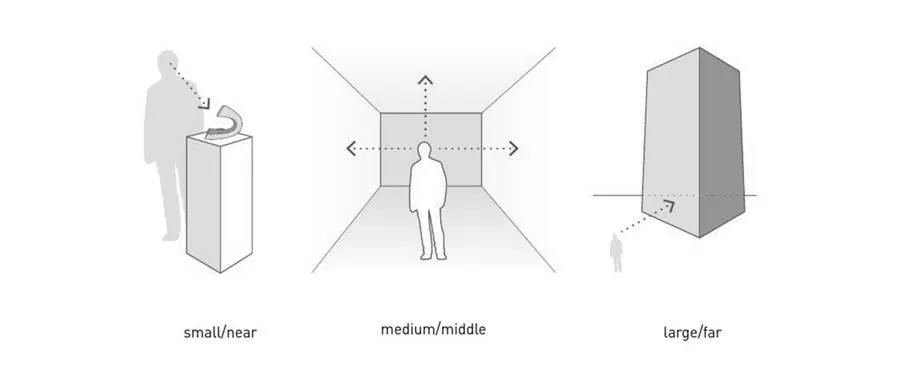

The perception of space, although mostly visual, is largely based on our relationship with scale. Our sense of scale is complemented by bodily sense, primarily through haptic feedback. According to the theories Alois Regel (1858–1905) and his Aesthetic Model, there are three main scales that we experience space; near, middle and far range.

· small/near: at this scale we are able to best understand complex curvilinear geometry. When we can take in the entire object, grasp it, rotate it, etc then we are able to build a mental map of the object and understand it much easier than if we experience only individual pieces at a time

· medium/middle: here we experience a portion of an object a time.Texture and clarity are important if the intent is for the user to understand the spaces or architecture as a whole. Curvilinear forms cease to be effective, because they go beyond the scale of the human body, and we can not form a mental map their entirety. Shading and contrast becomes important when understanding objects in a space at a distance.

· large /far: when experiencing architectural objects from a large distance, the ability for tactile understanding fades out. Simple forms and colour are most important. We lack the optical dexterity to interpret complex forms, and therefore high contrast forms or materials are important.