Charles Moore was the wizard who led us out of the sterility and self-importance of Modernism and showed us that we could go home again

Charles Moore, the Oberon, Merry Prankster, and Mystical Guru of late-20th-century architecture, had the ability to make the fantastical seem logical and the sensual seem necessary. Fascinated by modern technology and materials and in love with the beauty of vernacular forms for their deformation of grand orders into more comfortable and humble structures, he preached the importance of architecture’s ability to delight by sheltering, structuring and providing creature comforts. He also designed structures that zipped with neon lines and zapped with squares, triangles and octagons that had no business with each other, but somehow worked together to create great architecture.

I got to know Moore when, as an undergraduate at Yale College contemplating a life in architecture, I tagged along on a field trip the architect led through the countryside of Connecticut, Rhode Island and Massachusetts. It was a madcap careen past houses he had designed, the grand mansions of Newport, and the best fried clam shacks you never knew existed. Standing in one of the many churches whose columns, turrets and naves carried out with the economy of brick and white-painted wood held Moore’s attention, he pointed out to us how in this nave the light went ‘blub, blub, blub’, while in the previous church we had visited it had been more of a ‘bloooob, blooob, blooob’. We knew exactly what he meant.

Several years later Moore taught the introductory exercise in my first-year architecture school class. He had us design a ritual centre for the mythical land of Broceliande, ‘somewhere west of Oregon’, where celebrants skateboarded or roller skated in a counter-clockwise manner past seven shrines we were to design. This also made perfect sense to us. I have no memory what I designed, but I recall the instructions, so evocative and strange at the same time, as if I had received them yesterday.

All this is not to say that Moore came at architecture just as a stoned-out hippy. By the time I met him in the late 1970s, he had been Dean of Yale and held professorships at the University of California at Berkeley and Los Angeles, and was about to become the O’Neil Ford Centennial Professor of Architecture at the University of Texas at Austin. He received both a Master’s (for a project on Monterey, California’s adobe vernacular) and a PhD (for research on how water enlivens and informs architecture) from Princeton University. He seemed to know everything about every single building you could mention, and applied his erudition to both his teaching and his designs. He also was seriously committed to bringing architecture to the everyday life not just of rich people, but also of a wider population: he designed low-income housing and started the Building Project at Yale, in which students built community structures every summer.

Moore was also the ultimate collaborator. Despite the exuberance and distinct style he brought to his designs, he acted as a partner in a sequence of firms, including a period of polygamy when he flitted between offices in Los Angeles, Texas and Connecticut. The first of these was the best: Moore, Lyndon, Turnbull, and Whitaker (MLTW), in which each of the partners was an outstanding designer in his own right. It was with them that Moore designed his single-most influential project: the masterplan, clubhouses and condominiums, as well as several houses, at Sea Ranch. Grouped together in seaward-sloping volumes that the architects clad in cedar, these structures evoked local barns and farmhouses, but with geometries that crisped and scaled them up. Inside, supergraphics and large windows made for modern respites along this wind-blown stretch of coast in Northern California.

It was also with MLTW that he developed the kit of parts he spun out into houses on both coasts of the United States, and later collected as lessons in domestic architecture in his double-entendre titled The Place of Houses. His designs fit in the land and made interconnected spaces that in Modernist fashion did not devolve into separate boxes, but that in a more traditional manner provided a sense of belonging and framing. The quintessential experience in a Moore house is to curl up with a good book on a semi-octagonal bench from which you can look out into nature on three sides, and then look back into the house through openings in wood frames to see other rooms, staircases and windows at the house’s other end.

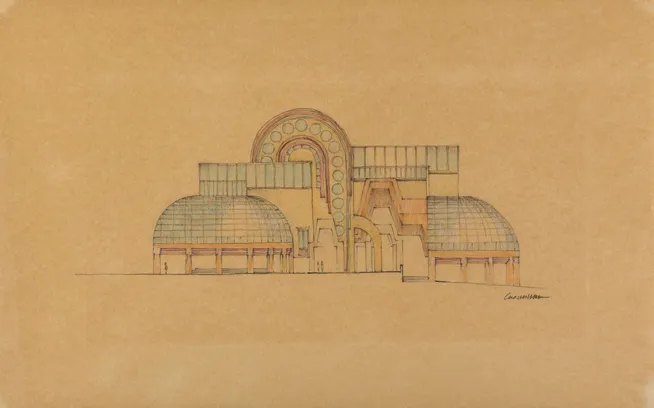

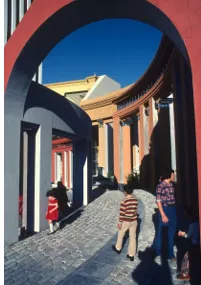

Architecture and life for Moore were theatre, and he designed the stage sets in which we could act out the roles we chose. Nowhere was this more true than at Kresge College at the University of California at Santa Cruz, where the dormitories turned into abstractions of Italian hill-town streets and the laundry room became a chapel, and at New Orleans’ Piazza d’Italia, an explosion of arches, zigzagging lines that turn out to be a map of Italy, neon lights and lots of water spilling around that evocation of the boot-shaped country. But his houses were also theatrical experiences, meant to frame private activities such as bathing under an aedicule (or ‘ridicula’, as he called it) in the home he built for himself in Orinda, California, as well as the many parties he threw in the houses he went on to build in New Haven, Los Angeles and Austin.

Endlessly peripatetic, Moore never settled down and never rooted himself. The same was true, to a certain extent, of his buildings. For all of their interpretations of local traditions and fitting into place, they were thin and restless things. Not for Moore massive monuments and tragic forms (even though he had taught for Louis Kahn). He wanted to have fun and thought architecture should be equally light-hearted, even if it was serious business.

As a result, many of his buildings have not aged well, either materially or in terms of their connection to the taste culture around them. That, in turn, means that, if anybody remembers him, they think of him as one of the Princes of Postmodernism (along with Robert Venturi, Michael Graves and Paolo Portoghesi) who reminded us to be sensitive to and accepting of history as well as of people’s lives, but also took architecture into the realm of commercialism and pop-culture evanescence.

Even worse is the fact that at least a generation of developer housing and commercial buildings imitated Sea Ranch and the MLTW houses, as builders found that the rotated squares and octagons, big cut-outs, and sloping roofs both sold well and were easy to build (they were, after all, based on construction vernacular). Large sections of the United States’ East Coast filled with a mess of grey condos and mass-produced houses that contributed little to a sense of place either inside or outside their thin skins. Moore and his firms contributed to the deformation of what had been such serious fun by diluting their designs to meet the budgets and tastes of clients wanting ever larger buildings – from Sea Ranch to the Haas School of Business at the University of California at Berkeley, a confused mass of morose forms huddling under oversized roofs.

But what I will always remember is the perpetual chuckle and smirk, the questions and the commentary welling up out of a deep knowledge of history, that emanated from Moore’s mutton-chop moustached visage. I will also always remember being curled up with that book, or looking at the sea’s perpetual assault of Sea Ranch’s cliffs from the safety of one of the homes I had rented there. Moore was the wizard who led us out of the sterility and self-importance of Modernism and showed us that, with the click of triangle and drafting pencil, we could go home again.

Comments are closed.