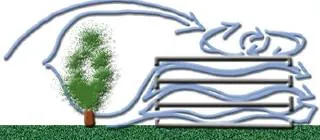

The configuration and pattern of massing of the built form can largely determine and modify the air movement both in and around the buildings. Depending on the relationship between the wind direction and that of streets and buildings, there may be variations in wind speed.

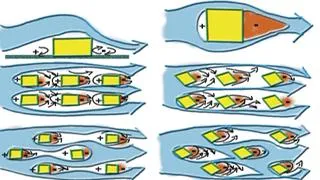

When large built volumes, or say a long row of buildings are placed perpendicular to the wind direction, then shielded zones are established between the buildings, where wind speed might be just a small fraction of the speed above building’s roofs, or in streets parallel to the wind direction. In this case the distance between the buildings have little effect on the speed currents between the buildings, the first row of buildings divert e approach wind current upwards, the rest of the buildings are left in wind shadow.

Thus two separate air flow regimes are created. The regional air currents flow mainly over the top of the buildings while in between the buildings a secondary air flow pattern is created as a result of the friction between the upper air currents and the building. This may be desirable in certain climatic conditions like the cold winters or hot summers when winds are to be avoided, but undesirable in warm humid climates when ventilation is required.

On the other hand when building blocks are placed parallel to the prevailing wind direction, the wind can blow through spaces between the buildings and along the streets with small retarding effect from the friction with the buildings. In this case, the interior of the buildings suffer from poor ventilation while the adjacent open spaces experience high wind velocities. Orienting buildings at an angle in relation to the wind direction can produce relatively homogeneous wind patterns around them, thus creating better ventilation, regardless of the relative position of buildings within the built up arrangement.

Comments are closed.