The Visual Nature of Space

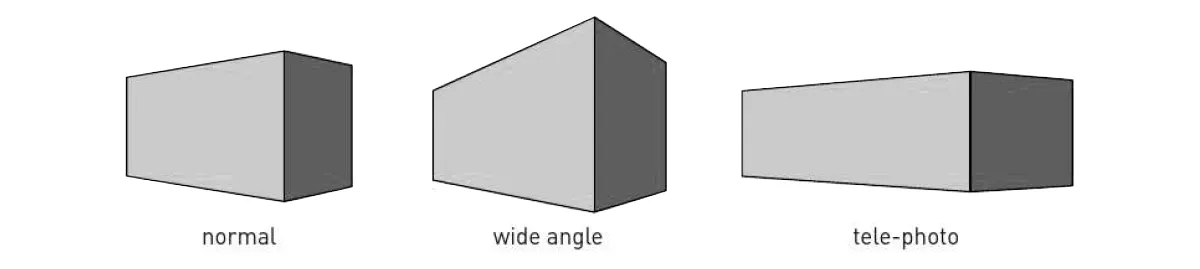

Experiencing space is a subtle act of the human body and mind. We use our eyes to visually probe a space, making thousands of subconscious computations every second. Wayfinding, orientation, direction, etc. all come from visual clues. The lens of our eye, with a 22mm focal length allows us to experience perspective space in a consistent and readable way. Our neck and eyes move, completing a spherical dome of information surrounding us at any point. But, when a slight change is introduced to this formula we start to question what exactly space is.

For me, this slight change in experiencing space was photography. For a few years I used an adjustable wide angle lens, appreciating the ability to capture as much space as possible. This allowed me to distort space, and experience it in a way that I never had before. But this distortion was an experiential lie. Transitioning back to a fixed 22mm lens, I learned that composition and spatial effects of differential spatial typologies was much more important than the ability to distort space. I felt the need to translate this back into my architecture.

Although I have been designing architectural objects for many years, it is not until I made these observations and conclusions that I can say that I started designing spaces. The paces were largely byproducts of a series of compromised design decisions, creating spaces that often felt like leftovers, rather than being the driver of the design. When considering how we experience each different space early on in the design process. I find I’m able to design spaces that are more pure, intimate, and spatially powerful.

Primacy of Space

Space is self evident, but the way we perceive it is not. Our brain has built in mechanism that allow visual inputs to be recorded and processed, outputting information almost simultaneously that we then act upon. The processing of visual information sometimes triggers cognitive loopholes. These loopholes are known as optical illusions.

The image below is an example of an optical phenomenon called shape constancy. Take your two hands, and hold them out in front of your eye. Move one hand double the distance away from your eye as the second, and make a mental note of their perceived size. Now take your closer hand and measure the farther hand with your index finger and thumb in a sort of pinching motion. Keep this measurement hand where it is, and bring the hand which was farther away back to your eye. Now you will realize that your brain allowed you to perceive both hands at almost the same size, irrespective of their distance away from your eye. This is the result of memorizing sizes of known objects, and not a spatial effect. There are numerous examples of optical illusions, but they do not deal with the true nature of space. Illusions trick our brain’s visual mechanics, and have limiting relevance on three dimensional spatial effects.

Most importantly I would look at euclidean geometry, rectilinear shapes, three dimensional geometry, and space and objects as being real. My intent was not to question the existential nature of space, but rather to investigate the way that physical spaces affect us as conscious beings. This is the true nature of space, the primacy of space.

Increasing Complexity

While conducting my research on the various topics of interest, most writing made a series of basic conclusions, which was then built upon to make further and more substantial claims. First, was that past generations represent how they think about space through images, and that visual art represented the spatial values of each culture. I would argue that by looking exclusively at images, one can not fully understand a culture’s understanding of spatiality. An example of where this was not true was in ancient Greece, whose architecture was much more spatially refined than their art from the same period. A second common assumption discovered in my readings is that our development to read space is directional, and that Greek thinking would not have emerged without Egyptian. Lars Macussen goes as far as to say that, “if a Renaissance image had popped up among the Ancient Egyptians, they would not have been capable of seeing it as spatial in the same way”. This conclusion also has its problems, as there is an abundance of new research that has been produced in the last decade that suggests there is an objective aspect to our spatial perception that is universal to all people. Another type of increasing complexity in spatial representation are the medium and techniques we use to represent space.

Comments are closed.